The Rest of What I Have So Far

A Matter of Curiosity

I walked Corin Graeme to the airlock, closed it from our side and checked with the 3d comp to make sure he had actually left the airlock.

I was about to say most of our clients didn’t play games, but that would be a gross prevarication. Most of our clients played games, and often lied to us.

There is something to the human psyche that when confronted with a heinous crime makes it slippery and skittish, as though by adding dishonesty to the whole thing, a decent human being could convince himself that everything was fine and the evil had never happened.

I empathized, truly, and yet—

And yet fooling others or yourself didn’t fix the yawning chasm and ache left by the loss of a murdered one, or the sense of betrayal that murder had been committed on one’s watch. Pretending couldn’t heal the world. The only thing that could do it was facing the crime head on, and bringing justice to the perpetrators.

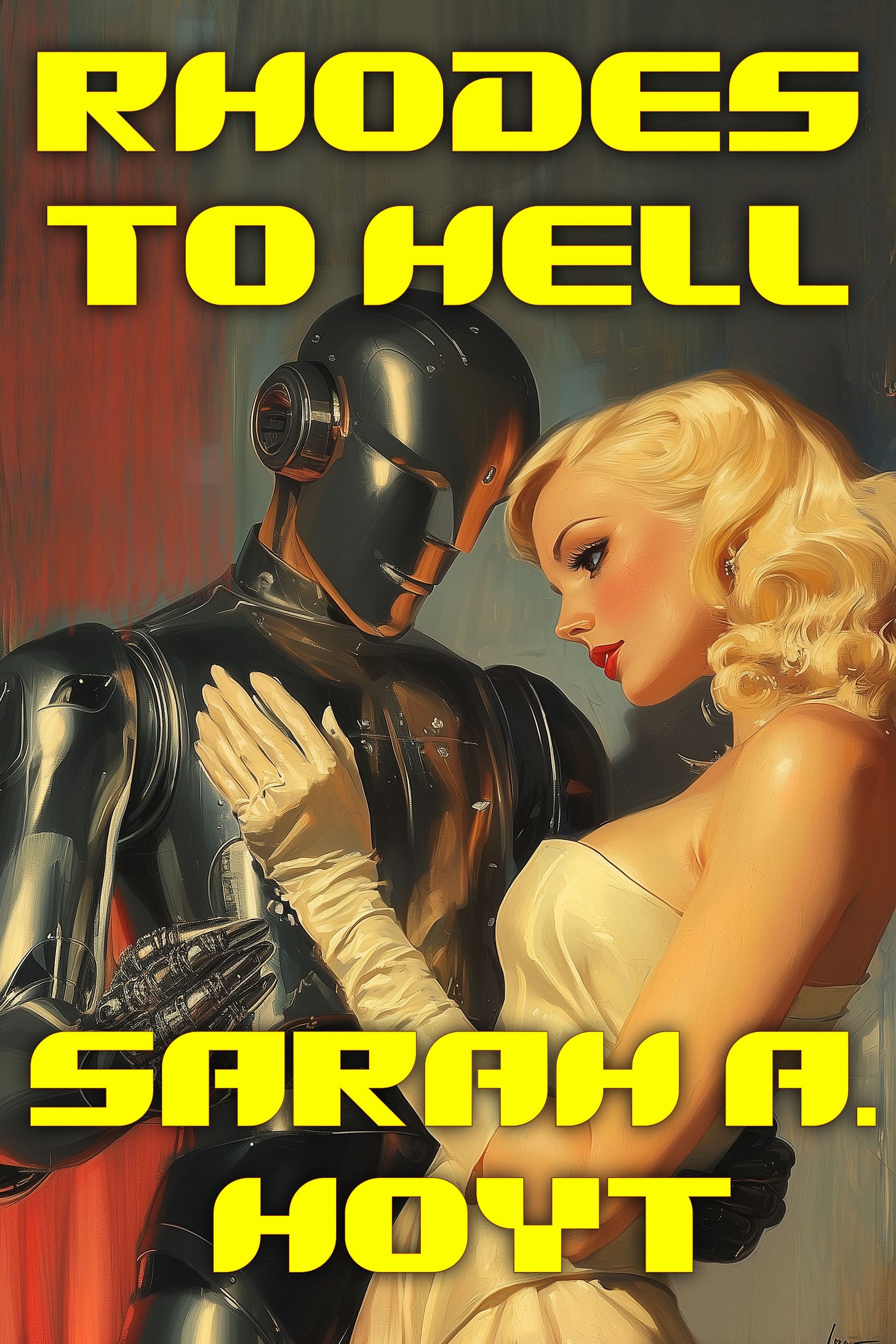

Which brought me back to the silent office, with the privacy shield off and Rhodes, feet on desk, staring at the ceiling. I knew this mood. He was thinking. Probably what he was thinking was how he’d got himself in the position of having to work, and how much more fun he’d have reading some strange disquisition on time travel or space engineering, or some otherwise impenetrable object.

I’ll say this for the borging process: you could take the brain out of the man, you could make the man forget what he once was. You could make him believe he was the main character of his favorite mersie series. But you could never – would never – make him into an entirely different creature, or complete erase his habits of thought. Or at least not this man.

He still sat as he did when he was human, and his thoughts followed the same predictable patterns. And all of it would make my heart ache, if I allowed myself to think on it. So, I didn’t.

I sat behind my desk, quietly, going over the last month’s accounting. Anything I said would send him careening in one of two directions. I had a bad feeling about the case, for all the money it would bring us, and if I knew that anything I said would make him drop the case, I just might do that.

But there was an equal and perhaps stronger chance it would send him hop-skipping-jumping into something head first, something he wasn’t prepared to do or face.

So I stayed quiet, till at long last something like a deep breath mixed with a sigh emerged from the borg. It was a phony of course. He couldn’t either breathe or sigh. He was learning the intrinsics of humanity and human emotions like a program. I wondered how much was remembered, how much faked, and if indeed there was any difference.

“Stella,” he said, in a tone as though the word hurt him.

“Sir?”

“Could you share that case gem with me? I’d like to know what it says.”

“I can read it and report,” I said. It was how we normally did it.

He frowned, the not flesh crinkling slightly to either side of his nose and giving the impression he had a headache. Could a borg have a headache? Considering most of them were never verbal after borging I doubted if anyone knew.

I flipped the button and for a long time there was silence. He can read much faster than I do, but I suspect he matched his reading to mine, perhaps for psychological manipulation reasons. I don’t know. I know we both pressed the off button at the same time. And I never fully understood Rhodes the Borg. I used to know the man who became Nick Rhodes, but while the patterns were the same, the creature was different.

“Report,” Rhodes said.

“I don’t see any reason to,” I said. “You read it when I read it. I feel as though I’m undergoing an examination.”

He shook his head. “No. I want to make sure I didn’t overlook some detail that’s important, some detail you’ll instinctively catch and realize it’s important.”

“Because I’m female?” I asked.

“Because you’re human and not borged.” His voice sounded waspish.

Took me a second of running that through my mind. Normally you couldn’t get Rhodes to admit that perhaps his recall might not be perfect, his mind absolutely unflagging, his whole being as purpose-ready and perfect as a drawn dagger. On the other hand-- On the other hand, his brain was all too human, and in the intersection of brain and body, how much had he lost?

“Very well,” I finally said, with ill grace. “Miss Sross’s murder was the only one investigated with full thoroughness. The other ones, they seemed to give up on when they realized that it was following more or less the same pattern: a wealthy woman murdered in the way that should have happened to a bio-mechanical construct, with an irate relative off screen, and the bio-mechanical construct who was supposed to commit the crime being completely devoid of evidence of having committed it or contamination caused by the killing itself.”

“Yes,” Rhodes said. More an encouragement to go on than a confirmation.

“Miss Sross was a created-child, the offspring of Zyre Boremon, who owns the largest spaceship builder in the Veil of Amphitryon Nebula.”

“Which would make him very rich?” Rhodes said. “Or at least so I suppose.”

“Correct. It would make Mr. Boremon wealthy beyond the dreams of avarice. I’ll have to check, but I suspect he owns most of the world where he lives, and that the only others in the world will be servants and dependents.”

“And Miss Sross was his only child. Why would she have a different surname, though, if she was his child, and he her only parent?”

I shrugged. “Not explained, but you’re right. There might be something to look into.

“At any rate, Miss Sross had no occupation, which is not rare for a woman of her age and class,” I said. I myself had pursued no occupation when I’d been Lilly Gilden, the daughter of a fabulously wealthy man. Not unless you counted dancing the night away and perhaps attending public functions an occupation, which it sort of was, but not the sort that made any money. Rather, it spent it. It wasn’t till I married Joseph Aster and was cut off by my father that I needed to work. Which at the time had been not much more than typing and keeping financial records.

After that… things had changed. And then… and then things had changed much more, when Joseph Aster had become a borg, very much against his will. I shook my head. I could speak about my regrets and fears to Rhodes, but what good would it do?

He seemed to have some block in remembering the murder of the man who had owned his brain before he had come into existence. Sometimes he remembered it. Sometimes we talked about it, when I could no longer hold it in. But the next morning it would be gone, like a dream. Something that had never happened.

I remembered all the time, of course. I remembered that inside that shiny carapace lived all that remained of the only man I’d ever loved.

And I remembered that, because borging was illegal in every human planet and jurisdiction – a logical step to discourage the practice, which was almost always done with the brains of unwilling donors, and which usually amounted to murder – and the penalty was death not just for the borgers, but the borged, and anyone who didn’t immediately denounce a borg, we were both living under a sword of Damocles, suspended by gossamer threads.

At least this Nick Rhodes realized his danger, and actively cooperated with me in keeping what he was secret.

His personal memory was a crazy hodgepodge of his life as a human, but also of the Nick Rhodes series set five thousand years ago. He managed to understand enough to our current world to have a shrewd eye for criminality and the ways it hid, and to be able to hide himself. I couldn’t ask for more.

It wasn’t given to me to unwind time.

I sighed and went back to narrating the investigation into Ms. Sross’s murder, “She became fascinated with serial murderers about three years ago, judging by interviews with her associates. And LL must have done a lot of traveling and questioning, since there were twenty or thirty interviews on the file. Her interest was not… rational but romantic. The idea that people could kill many other humans and get away with it, even when there was already a world-queen and a more than rudimentary civilization fascinated her. It felt like being in contact with the primitive in humans. Perhaps a little morbidly, she read everything she could find on various mass murderers, and went to various places to consult experts on serial murderers in… well, in New Oxford, for one. She talked to just about everyone there who could shed light on these matters, ranging from psychologists to historians, to professors of investigation.

“She also visited Aureus 3 to talk to the renowned retired investigator Morraya Rhone. Strangely, we don’t have an interview with her in the paperwork. We might want to talk to her.”

Rhodes groaned. “We’re going to have to talk to a lot of people.”

“Yes,” I said. And then reluctantly, because I still wished he’d let this case go. “And even if we do it via holographic calls, the long distance will be expensive. Though half a million Lyr will probably see us through it.”

His blue eyes flashed. They could literally do that, since they were lights installed on the sockets of his perfectly molded face. However, I never fully understood how he made them flash.

Nothing I had read about borgs indicated they could flash their eyes in tune with their emotions. Then again, there was very little written about borgs, other than sensational crime literature about the process of borging. And even then things were kept pretty hazy. After all, you wouldn’t want anyone to get the idea of how to make a borg, or that such a thing might be achievable let alone desirable.

I was engaged in an experiment in discovering the various ways that borgs reacted and behaved, and in studying up close and personal the effects of borging on an unwilling victim. An experiment I’d much rather not be performing.

Staring at Nick, I wondered if there was inevitable decay, and if I’d lose him by inches without knowing until it was too late and it was all unretrievable. I also wondered where this would lead.

Sure, I could keep him with me and keep from losing him utterly, but was there a future for us? Once upon a time, with the brain now locked within Nick Rhodes, I’d thought of having children, a family, a life away from being itinerant Private Eyes.

Now…

Now I held on to each precious moment where I had at least part of him with me, and knew it might be all I ever had.

He turned to me, and his eyes seemed brighter. “The other crimes weren’t investigated at all?”

“Not really. They were afraid of angering the next of kin, which to be fair happened with Ms. Sross’s parent. He took exception to having his financial life looked into. And it was all for nothing, since it showed he was in absolutely no financial distress, and not in need of the infusion of cash he got in compensation for his daughter’s death. In fact, you could say he barely noticed the infusion, given the immensity of his fortune. He merely wanted to make Lived Lives hurt.”

Rhodes nodded, as though this made sense. “And the others?”

“As far as I know they did some very hands-off looking into the relatives, not enough to excite anger. And the story is the same everywhere. The relative paid was on good terms with the deceased, though one or two expressed distaste at the deceased’s hobby, but one doesn’t kill a loved one because one disapproves of his or her pastime. Or at least… Well, there wasn’t that level of upset indicated.”

Rhodes was silent a long time, then said, “Can you assemble files on the others? And perhaps we should arrange to talk to Jim.”

I nodded.

He turned on his book hologram and went back to his position, feet up on his desk, reinforced chair tilted way back, while he lay practically prone, perusing the ceiling.

Good for some, I suppose.

Me? I went to work.

****

Jim was James Brighton. I knew him from my college days in the world called New Oxford. You probably know him as one of the most influential news mediators in the business. Yes, that James Brighton, whose particular blend of news is syndicated through hundreds of worlds.

In many ways, for those worlds, he is the news.

After all, what we know as news is in fact a careful compilation of the happenings that we think are important or relevant to the rest of the human universe.

You could spend the entire day reading just the headlines for a tenth of the human universe, and never getting to the end of the day before the next headlines showed up. Even mediators couldn’t read all of them.

So they developed…. Sources, and people who fed them what they might carry, and a second sense for what would interest their audience.

It was always like that to an extent. Twentieth century experts said even in that dark age there was a newspaper who tagline was “All the news that’s fit to print.” And according to at least one thesis I’d read when I was in college, their decision for what was fit to print had more to do with their ideological bend than with what might interest the public. At least that had changed.

People like Jim had a very sharp second sense indeed. His brand of picking and focusing the public interest had earned him wide following.

Not bad for a young man from a backward planet, who had attended New Oxford on scholarship, and been rightfully snubbed by everyone from a wealthier background.

My husband Joseph Aster had saved Jim’s reputation and perhaps his life. This, despite having paid back in some ways many times over, made Jim think that he was in our debt. So, despite his crazy, erratic schedule, he always made time for us.

All the same it didn’t hurt to send him warning and ask for a time to talk to him.

He replied to my ping almost immediately, which given the pace of intergalactic conversation was pretty difficult. He set an appointment for late evening ship’s time and probably his own time, considering that we kept the ship in New Oxford time, which is where Jim had his office.

And then I threw myself into the network of investigative connections for the victims.

Look, they weren’t major celebrities, so they weren’t that hard to find.

Even major celebrities, known in all the human worlds were not really major. Again, it’s the same reason we need news aggregators.

When you have thousands of human colonies, on separate planets, some with populations larger than the population of old Earth ever got, you could be a divine sculptor, a musician kissed by the muses, a painter of astonishing skill, and most humans in most worlds would never know of you.

Fame was restricted, small. Sometimes everyone in your profession would have heard of you. That was fame indeed, and of necessity meant you were at the top of the skill and talent tree. But not even James Brighton was known throughout the human universe. A few news hubs in maybe a thousand planets. To the rest he was unknown. A non entity.

As wealthy as my father had been, and as much as my picture as a young socialite had been splashed all over the galaxy, I was still not known most places. Which was good, because even with modifications, people who knew me before might very well recognize me.

Fortunately the human universe was vast and varied, and even the largest celebrity was minor, when you considered every world.

These people weren’t even celebrities. Not really. In Aibell Sross’s case, her parent might be considered that but only in financial and transportation circles. For the rest not even that. I had to search the nets, and in one case the civil records of their world of residence before finding much of anything.

So it was a slog, and you don’t want every detail. All told it didn’t advance our investigation any. Not at that point. But I’ll give it to as I gave it to Rhodes.

About two hours before our appointment with Jim, I turned off everything on my desk, except the pad onto which I’d taken notes.

“Mister Rhodes,” I said.

He sighed again, the phony, but got his feet off the desk, and sat up, turning off his book. The cover, visible to me, revealed he was reading an old spy novel, Amid the Other Kin. Something from the late twenty first century, which I’d heard described as post-modernistic and barely coherent. Not that this had ever stopped Nick Rhodes from reading things. He was an indiscriminate reader throwing everything into his mind with the enthusiasm of a vat cultivator collecting chemicals.

“Yes?” he said. And then, as though I might not understand. “Report.”

I reported. “We already know everything that can be found online about Miss Aibell Sross. Her parent is so wealthy that he probably didn’t feel the payout, though it might interest you – at least on the emotional side – that he used the pay out for her death to start the creation of another child, whose only parent he is once again. It is not known whether this one will be male or female.” I paused. “Because I thought it might be of interest, I took the time to collect the pictures of the victim and the payee for each of these women.”

“Very well.”

I pressed the buttons on my desk, so that it projected 3D images in the center of the room. In this case, Miss Aibell Sross and her parent.

Aibell was petite, blond, with lively blue eyes, and wearing something long and flowing in bright pink. Her hair was gathered at the back of her head, and from the angle I was at, it was impossible to see whether in a ponytail or a bun. She seemed to have stepped out of an historical romance of some sort, the sort of young woman who would have a laughter like the tinkling of bells, and a high and sweet voice.

Her parent looked nothing like her, which was both unexpected, since he was her only parent, and made perfect sense, as people who had children created to spec often dictated the appearance.

I made a note to myself to find out who miss Aibell Sross looked like, since the appearance of a made child was often an homage, to either a grandparent, another ancestor, or even a long lost love of the single parent. Zyre Boremon, the parent was a tall man, with a high-bridged nose, blue eyes and dark, thinning hair. From his appearance he was late middle aged. Perhaps 200 or there about. He wore a one-piece suit in the style of a hundred years ago, in dark blue. Which might mean something or nothing at all. After all, styles changed independently in various worlds. I’d once visited – with my father – a world on the periphery where the style for whatever reason had settled on shorts and nothing else for men, with a brassiere in addition for women. I’d seen a lot of paunches and excrescences on that trip, and returned convinced that all humans, ever, should be covered in swathes of fabric, so the shape underneath was mostly guessed at. For the sake of other humans who had to look at them, of course. I’d gotten over it, but not immediately.

At any rate, Boremon didn’t give the impression he needed yards and yards of fabric. Either genetic manipulation or plain old surgical sculpting indicated that from the neck down he could be mistaken for an athletic man in his twenties.

Nick Rhodes made a sound that I didn’t fully understand, except as a signal to move on.

“Miss Talira Tyse, from New Quebec, was the only one of these that had a legitimate reason to be in the planet. She was a creator of crime mersies, both true crime and fiction, and she was there, according to her father, Arrymo Coley, to refill her well after finishing a series of particularly difficult mersies.” I didn’t mention that she’d once upon a time been a consultant with the Nick Rhodes show. It hardly seemed worth it. I never could fully understand how much the borg that believed he was Nick Rhodes was aware that his identity was wholly appropriated from a fictional character. Sometimes he gave the impression of knowing this perfectly. Other times, he talked about it as though he were the actual Nick, the fictional character, and there had been no other, ever. I preferred not to go down that rabbit hole, particularly in the middle of an investigation. “Their surnames are different because in New Quebec, the children take the mother’s surname.”

I flipped the button on the desk.

Miss Tyse was small, on the slim and slight range of human female. She had close cropped dark hair and dark eyes in an unremarkable oval face. The 3-d image was obviously captured from some public appearance – she’d received a lot of prizes for her work – and had caught her in a two piece, dark blue suit, that molded her body but somehow managed not to be even vaguely sexy. I’d say there was something predatory in her smile but that might just be my feeling. There was definitely something predatory in her father’s smile, a sort of hunger that couldn’t be put into a neat slot.

“He didn’t need the pay out for her death?” Nick asked, and I didn’t blame him.

“Not according to the investigation,” I said. “He is a galactic communications specialist, and he and his wife live very well. They paid for tuition for all their six children to New Oxford. But I shall ask Jim if he’s heard anything.”

Lady Patry Rigalan looked exactly as you’d expect. Tall, imposing, with dark brown hair piled up on her head in a way not seen anywhere without an aristocracy of birth, ever. She wore something dark and layered and complicated that might have been a gown or merely a coat over a gown. It was hard to tell, since the color was about the same, and in hologram they bled into each other. Her brown eyes seemed to look down on us with disdain, like she’d always be better than the rest of the world.

“She is a lady by virtue of her father, the Duke of Huldin, which is a monarchy, subjected to the Star Empire. Her husband is a financier of some renown and wealth, but his fame is pretty much confined to Huldin. Her marriage,” I said, feeling sympathy, since the same had happened to me, “was considered a mesalliance, and her father disowned her.” I noticed that Rhodes sat up a little straighter at that, but I couldn’t tell if it was because he had identified that part of my own personal history through some dim memory, or if he imagined this might be a reason for her murder. Which wouldn’t precisely be wrong.

“She and her husband did pretty much everything together, mostly living in the country in Huldin, in a large mansion with a larger farm attached, and raising horses and dogs. Sometimes they went to the outer planets to hunt some animal or other. Apparently the fascination with true crime was new, and also shared by both, but her husband, Tine Meson, had some emergency at his banks prevent him going with her to the planet. As with Miss Sross, the payout was almost incidental, but Tine Meson was said to be heartbroken at the loss of Lady Rigalan.” My heart twitched a little in sympathy. I knew what it was like to lose a very beloved spouse.

I flipped the button and an image of her husband appeared. He was cut on the same large lines, blond and bluff, and was laughing in the captured hologram. I imagined he was laughing at some joke that Lady Rigalan had made. I wondered how much he laughed now.

Rhodes was leaning forward on the desk, staring at the image with an avid interest. He nodded to me, as though to say he was done.

“Free citizen Arbian Midere,” I flipped a button to show a woman who could have been a ballerina, from the long, dark hair caught up at the top of her head, to the muscular legs guessable through the tightly molded pants. Her tunic-blouse was loose and printed all over with something that might be colorful seashells or some exotic life form. She was captured mid-stride, up on the tip of her left foot, while the right was just slightly off the ground. Her lips were parted as though she were speaking, and her eyes had that “oh, just one more thing” expression.

“She was an expert in the cookery of 20th century Earth. She’d spent fifty years studying all the archeological records, both recipes and food that happened to be preserved for posterity, mostly through some disaster or accident, and recreating it. This sometimes involved going to various different worlds, to try to secure the type of wheat or potatoes that’s supposed to have grown on old Earth. Her wife, Ylivea, is a restaurant creator. She comes up with concepts, sets up the restaurant, in whatever world, makes it a going concern, sell it, and moves on to the next restaurant and concept.”

I flipped the switch to show Ylivea Midere. I’d heard of spouses looking alike. These two looked enough alike that they might have been identical twins, except that Ylivea’s hair had a hint of red, her eyes were blue, and she was quite obviously heavier. “She is supposedly wealthy enough – she is certainly successful – that she didn’t need the payout. She also,” I said and realized I was frowning, “is said to have stated that she had no idea her wife was in the Lived Lives purview, or that she had the slightest interest in mass murderers of the late nineteenth century.”

“Which might be true,” Rhodes said. “Or it might be because she found her wife’s interest unpalatable and was trying to keep it from public knowledge.”

I nodded. He tilted his chair backwards. “Go have dinner, so you have time to finish before James calls.”

****

Having to eat alone was one of the great disadvantages of living with a borg. Rhodes did not eat and I couldn’t demand that he take an hour a day just to sit with me while I ate. Which was a pity, as dinnertime used to be one of the times that my husband and I discussed murders or other crimes in the news, or mulled over the interesting points of the case we were investigating. More than one interesting idea or lead to pursue had come from relaxed talk at dinner time.

Strangely, and perhaps to compensate, Rhodes made it a point to cook for me. Perhaps because he couldn’t eat, he’d started finding it interesting to research food and buy new and unusual compilations of recipes, which he then used to program our cooker, sometimes with adaptations to avoid exotic ingredients.

That night, the cooker delivered coq au vin, cooked to perfection, on a bed of wild rice. I ate while trying to figure out some breakthrough on my own.

Part of this was ridiculous. Why would I come up with some breakthrough, when it was Rhodes whose brain was sought out by the people hiring us, and Rhodes who was supposed to be the genius.

But – though it hadn’t happened yet – it was perhaps possible that my fully human nature, with an organic body gave me some sort of advantage over the genius brain encased in metal.

I turned over the whole thing in my mind, over and over, like someone rotating an object to fully understand it.

Look, I’m not a crime aficionado. Which might sound funny from someone who makes her living from crime, or at least the investigation of it. But perhaps that is the point.

Crime, to us was what paid the bills, put food on my table, and arranged for the very expensive compounds to be delivered which would keep Nick Rhodes alive, or a close facsimile thereof.

It wasn’t something that happened to people long ago and far away, but what happened to people who came in search of us, looking for help, and with a problem big enough to justify the big pay out we needed.

The mentality of people fascinated by death was completely alien to me, particularly death long ago and far away. The people who had been murdered would all have been long dead anyway, and completely forgotten, except for having been killed in a sensational manner. So, precisely what was the point?

But I knew it happened. It wasn’t just the nineteenth century, either. Each century had its passel of horrific unsolved murders, and if I had to guess there were various amusement parks of sorts where these were recreated for the amusement of well-heeled ghouls.

I didn’t search to confirm this, but it took effort.

Of the people who’d been killed, unless the relatives were paying Lived Lives itself to be rid of their supposed loved ones, and the whole thing including the payout was a ruse, if in fact they’d all been killed to hide one singular murder, Miss Talira’s father would be my guess. And it was stupid because it wasn’t based on anything much but the fact I didn’t like his expression.

Grateful that no one expected me to be the one to make sense of this, I went back to the office, to find that Rhodes was reclining in his chair, with his feet on the desk. But he hadn’t turned on his book.

His eyes flickered gently, the blue light sweeping the ceiling.

Which was interesting, since in his case this normally meant he’d found something interesting that he believed would allow him to solve the crime.

He put his feet down at my entrance, which meant he wasn’t deep into the mental stream of his thoughts, and his face did a convincing impression of a smile, without moving much at all. “Did you have a good diner?”

“Yes, thank you.”

“Good. Is it about time for James—”

The com on my desk blurted, indicating there was a call from James coming through. It was on a protected circuit of course. To be fair all of James’ calls were, pretty much. I pressed the accept button, and an image of James appeared in the middle of the room.

Jim was a slim, dark man, with unruly hair and a mobile face that perfectly reflected his thoughts. He sat at a desk piled high with data gems, papers, a couple of coffee mugs, and a few other beverage containers. I had never asked, but I very much hoped that he had someone come to clean every once in a while. The change over in the various containers and the position of piles of papers and gems seemed to indicate it, but honestly, maybe some just fell to the floor, now and then?

One got the impression that Jim lived at his desk, surrounded by both the debris of living and the debris of his profession. And that he completely lacked a social life.

While this might not be absolutely true, it probably was true in the essentials.

He smiled at me, and gave a look, out of the corner of his eye, towards Rhodes. Then looked back at me. Almost surely there was a hint of pity at the back of his eyes. I chose to ignore it. I knew why it was there, and frankly, he’d known both of us back when, and had been one of very few people to congratulate me on my marriage. But if I acknowledged it, I’d be required to do something about it, and something about my life.

You see, I could endure working for the borg, and concentrating on the cases, and solving one case at a time, and slowly improving our ship and our life.

But if I thought about what the situation really was, and how devoid of any hope for the future we were, I’d probably start crying and never stop.

Instead, in a crisp, clear voice, I gave James a summary of everything that had happened since Colrin Graeme had come into our ship, including what I’d been able to find about the victims and their close relatives.

He looked pensive. His fingers tap danced on his desk, around the piles of debris and paper. He frowned at the hologram that only he could see, then he turned back to look at us. “The only one I know anything about, off the top of my head, is of course Zyre Boremon. He’s been in the news a bit, mostly for his business, though—” He shook his head. “I’ve set a search to run on the others, using my resources, and we should have an answer in a few minutes.”

“Though?” Rhodes said, before I could say it.

“Though is wife was murdered, about fifty years ago. And he never remarried. A lot of people interpret this as meaning that it was a great love affair, of the sort that can only be dreamed of. He also had his daughter, Aibell Sross, created to look exactly like his wife, which occasioned both suspicion in the minds of the cynical, and much romantic heart clutching on the part of those inclined to see endless love in everything.”

“But then why not use his wife’s genetic material? In either case, I mean,” Rhodes said. “Whether he wanted his wife’s look-alike for some disreputable purpose, or because he wished to memorialize his wife, this would seem the most logical to do.”

Jim shook his head. “His wife was murdered and incinerated. It was a big case in Taceanus, where they lived. Genetic material wasn’t available, and apparently he didn’t have any in storage.”

Rhodes’ lips twisted, and I got the impression he still found something wrong with this, though I wasn’t absolutely sure what or why. It’s entirely possible that he thought people that rich would have some of their genetic material in storage in case-- I don’t know. Someone suddenly borged them? We hadn’t had any of Joe’s genetic material. Then again, we hadn’t been wealthy. Just itinerant PIs solving crimes all over the human universe. For that matter, none of crimes we’d solved prior to Joe being borged had been murder or divorce, that is the big cases that brought in the most money.

“Why is her name different from his?” I asked. “Is it his wife’s name?”

“The surname? No one seems to be absolutely sure. She once said—” He shrugged. “No, it wasn’t his wife’s surname, nor was the first name her first name, but those were the names he gave Aibell at birth.” He shrugged. “Could be something as silly as making sure she wasn’t identified as his daughter at first hearing of her, particularly when young and vulnerable to kidnapping. Some very wealthy people do that.”

I inclined my head in acknowledgement. I had a vague memory some of dad’s friends had done exactly that. Though the idea that Zyre Boremon done that while at the same time letting it be known his created child looked like his late wife seemed to defeat the purpose. But I wouldn’t judge. A lot of these things became known through a rogue nanny, governess or school director.

While the fame of humans was often confined to the world they lived in, in that world it could be pretty pervasive. And the local media was always hungry for information about their celebrities.

“Ah,” James said, spinning his chair and looking at a part of his desk we couldn’t see. He did some tapping again, and the hologram in the air above his desk changed.

It wasn’t readable from our side, and it was to blocked by his body, anyway, instead of between us and him. I hated when the readable holograms were in front of people’s faces. Even when you couldn’t read them, in privacy mode, the scrolling of characters across someone’s upper body and face gave the impression of stigmata of a particularly mutable and animated kind.

In this case, it was just a fog of sorts in the air, scrolling past. He stared at it for a long moment. Then he looked back at us.

“Two things strike me as interesting, that are above and beyond what you told me. One is that the new child that Zyre Boremon had made is also female and looks like Abeill. This might or might not mean anything, as he might have left the choice up to the people handling it, and they might have picked the strongest embryo. The other is that Arrymo Coley had apparently joked about killing his daughter for her life insurance. This is mentioned in an article, in which he says he’d never have done such a thing if he suspected she might be taken from him.”

Rhodes made a sound deep in his throat. “She had life insurance?” he asked. “In addition to the payout given to him by Lived Lives?”

“Some. Doesn’t seem like a significant amount, compared to what she brought in from her work, or to his own income. It’s possible, if not probable, that his joke was actually just that.”

Jim leaned back on his chair. This being an hologram of his, in the middle of our living room, what we saw was only what showed of him down to the desktop. So, when he leaned, we saw more of him, as he was mostly reclining at the level of the top of the desk. He put his feet on the desk, the way Rhodes did, but with slightly more care to fit his feet between a coffee cup and piles of papers. There was a hole on the bottom of his left shoe, which was ridiculous given his income, and his profession. He looked, not at us, and not at the desk, but up somewhere that must be near the ceiling of his room.

I assumed he was looking at text hologram floating at about that level. His brows furrowed between concentration and worry. “Now, Lady Patri Rigalan…” Jim frowned at what he was looking at. “It might be nothing, and I hesitate to put much into it. I never share this type of news, or push them, unless the person is of political interest and involved in campaigning or something like, but… She’s been dead almost a year, and her husband, Tine Meson, is rumored to have been seen at all the fashionable places in New London with a young woman, Loxley Lorson, who is the youngest daughter of the Earl of Catlow.” Jim did something to his keyboard, and a hologram appeared in front of his desk, floating midair, so her feet were at the desk level. “This is the Honorable Loxley Lorson,” he said.

The Honorable was… Tall, like Lady Patri Rigalan had been, but the resemblance ended there. While Lady Rigalan had been more imposing than handsome, let alone pretty. Lorson might very well have been a mersi star, tall and beautiful of face, and slim except for bulging in all the right places. And she wore one of the briefest gowns I’d seen outside someone in the business of selling their appearance.

As captured in the holo, her hair was loose in a cloud around her face, and she was looking over her left shoulder and laughing.

I made a face. Jim was right. There might nothing in it, of course. They were both wealthy people, in the same political unit, who probably ran in the same circles.

“Again,” Jim said. “I want to emphasize there might be nothing whatsoever in it, and it might all be just a construction of news selectors who specialize in minor local celebrities. His history would, of course, invite scrutiny.”

“Of course,” Rhodes said. “And anything on Ylivea Midere? Anything suspicious, I mean?”

Jim shook his head, still staring up. I suspect you needed to be news aggregator, or of course a private detective, to show that much regret at the fact that something was above board and beyond suspicion. “No,” he said. “Or at least nothing I can find, which likely indicates there is nothing. I’ll keep a search going that will ping me, should her name come up in something, but it is very likely that nothing is indeed to be found. She started three new restaurants, all of which have probably made her more, in the six months since Arbian died than the payout from Lived Lives.”

We chatted for a few more minutes, but nothing of consequence came out. It was obvious nothing of consequence would come out, in fact, and Rhodes openly lost interest in the chitchat, and turned on his own book-hologram, and went back to reading.

Jim’s gaze went over my shoulder, to stare at Rhodes. He chewed the corner of his lip and seemed to be deep in thought for a moment. Then he said “Lilly, how are things going?”

The cue to me was his calling me Lilly and not Stella. Lilly was a young woman who’d married an itinerant interplanetary investigator called Joseph Aster, who was just starting to make his fame as a PI. She was a fairly useless young woman, because she had been born the daughter of a very wealthy man and never had needed to work or even think. She thought of course, but mostly of how to look good and display to advantage, since the minor-celebrity news aggregators had an interest in her. At least till she married Joseph Aster, when she had found her talent for typing and accounting came in handy, even if not essential to her husband’s business.

She had been happy, most of the time. The Asters had been not-exactly church-mice poor. But most of the money that came in was invested back in the business. And they had plans.

Until, of course, Joseph stopped existing.

And then I’d become Stella D’Or, Nick Rhodes’ faithful associate and leg woman. Not meaning that I was interested in legs – I wasn’t – or that my legs were interesting, though at one point several photographers seemed to think so, but that I was the one responsible for all the legwork.

Obviously a borg couldn’t leave the ship, or be seen without the protection of the privacy veil. Instead of Joseph’s old, active investigation style, Nick was forced to stay behind in the ship and think, and everything that needed done outside, I carried out.

I’d visited a dizzying variety of worlds, had experiences in places that even Daddy’s money couldn’t have bought me, in places where Daddy would be very surprised if not outright shocked to see me. I’d gotten in fist fights with strangers. I had visited morally dubious places. And I might or might not, by accident in a singular occasion, killed a human being.

If Jim wanted to know about Stella D’Or I could have chatted about the last case, or the things I’d learned to do since then.

But he’d asked Lilly. I looked up. I met his dark eyes. Perhaps it was my imagination, but he seemed tired, more deflated, since we’d worked on our last case and had interviewed him. He looked like he lived a thousand years since he’d helped me hide Joe’s borging, and create our present business. I understood why I might look that way. But why did he? “Oh,” I said. “I’m doing fine. I can’t complain.”

He looked like he’d say something else. But he didn’t. He kept looking over my shoulder at Rhodes. He opened his mouth, closed it, then nodded once, and said, “I see.”

I was very much afraid he did.